Martyn Cuff is Head of Operations for Allianz Global Investors Europe. The Operations team covers Mutual Funds, Segregated Accounts and Fund Registration and is based in a number of key European locations. Martyn has 21 years experience within the investment management industry. During this time he has operated within both the front and back office at private client and institutional fund managers. Prior to joining AGI Europe, he was a founding partner at a boutique investment consulting company, CSTIM, and before that he worked at Ernst & Young. His early career was spent at Barclays. Martyn is an active member of the European Fund Industry, contribution to various forums and publications.

ABSTRACT

From where fund management companies obtain their operational support has become a more complex question over the past twenty years. To a large extent this is simply a reflection of developments seen in the broader business world in terms of changes to business models and the need for operating models to keep in step. Allied to this is the greater range of sourcing options now open to companies, largely on the back of the technology revolution. It is clear that further change lies ahead with business models becoming ever more specialised and collaborative.

Coping with these developments puts a lot of pressure upon fund managers to ‘glue’ together these more fragmented operational elements to achieve control, efficiency, risk management and output yet maintaining sufficient flexibility to adapt an ever increasing pace of business and consumer change. Not all operational departments are equipped with the sufficient competencies and processes to undertake proper supply chain management and thus get the most out of these new sourcing options.

This article firstly looks at the broader sourcing environment and then considers what fund managers need to have in place to cope with the business and operating changes that are taking place.

Keywords: fund management, operating models, collaborative, supply chain management, sourcing options.

INTRODUCTION

Companies are made up of individual functions that must not only be successful in their own right but also work in an aligned fashion or ‘glued’ together to deliver on the corporate objectives. This kind of total system thinking, or to use the more formal description of supply chain management, is key to achieving world class operations. The problem is that this thinking is not always valued within fund management companies particularly where outsourcing has taken place. Instead, fund managers have been known to point their finger at that their outsource partners where results are not as desired. Whilst there is undoubted evidence that the service provider community need to improve the quality of their services, fund managers also need to look at themselves to see whether they are taking the lead to put in place the right mindset and tools that promotes the appropriate environment.

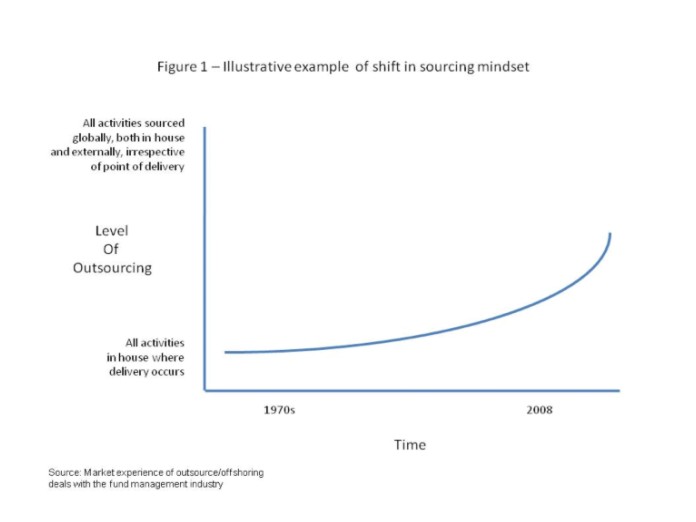

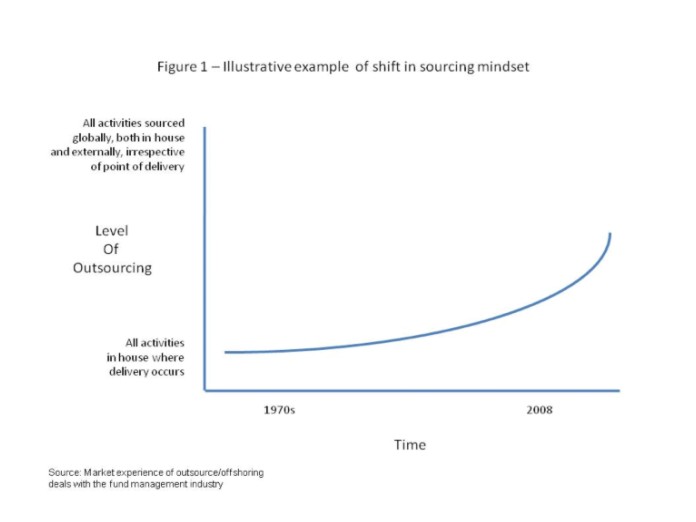

Over the last twenty five years there have been a range of approaches adopted to answer the question of ‘How best to arrange our sourcing’ within fund managers. In the 1980s, the sourcing question was not top of the agenda, since the majority of fund management companies did most things themselves. Even where it was considered, thought did not stretch much further than outsourcing of custody. Since that time, there has been an exponential increase in the rate of sourcing consideration. In the early days in fact it was not ‘sourcing’, the description was simply ‘build, buy or outsource’. Nowadays the in-vogue terminology is ‘sourcing’ i.e. ‘what is your global sourcing approach?’ Figure 1 represents in simple terms how this trend is accelerating.

Supply chain management only becomes a key necessity if it is true that this increased complex sourcing picture is going to be part of future management challenges within our industry. There are two sources of evidence to draw upon to support this view: firstly within the fund management industry and secondly the broader business environment.

WITHIN THE FUND MANAGEMENT INDUSTRY

Asking a few questions shows that the asset management industry is already on the journey to a more fragmented operating environment:

- When was the last time a fund manager embarked upon a back or middle office system development and build? If not for some years then one of the reasons is quite possibly that this system build has been outsourced to third party software vendors e.g. Sungard, DST, Simcorp, Bloomberg etc through the usage of their generic products

- When was the last time that a fund manager decided to build and run his own data centres and business continuity facilities? If not, then there is a fair chance that the reliance is placed an external third party IT company

- Was offshoring seriously considered ten years ago? Not in a widespread fashion, but its more difficult to ignore the subject today

- When was the last time that fund managers were looking to bring back in-house activities that were undertaken by third parties? In general not for some years which indicates at least some level of willingness to leave these activities with others

The asset management industry is at the leading edge in some subjects such as allocation of capital to maximise return, however it is not always first to test out new ways of running its own businesses for maximum efficiency. Therefore it is worth looking at the wider business environment to identify any indication about the future development of sourcing - Dell1 and Vodafone2 are useful examples.

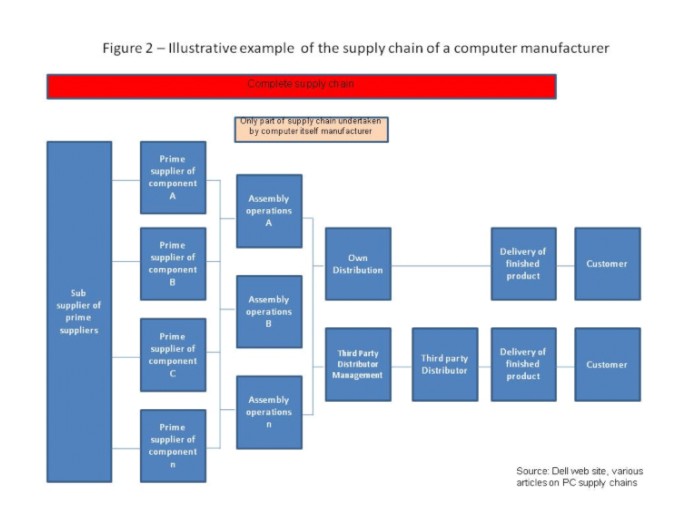

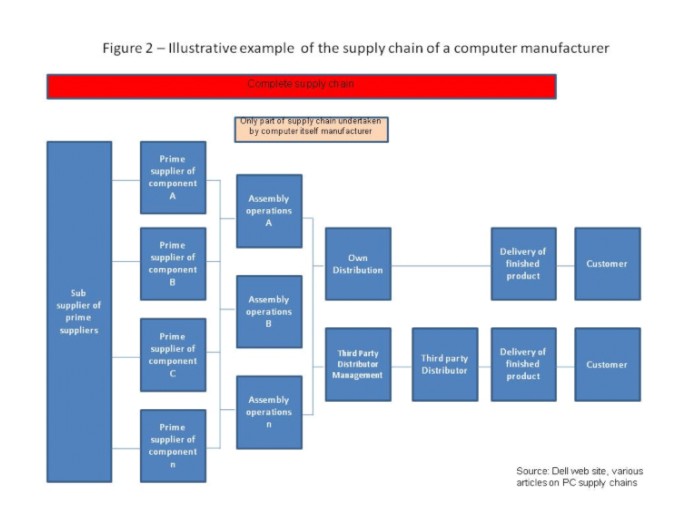

Like most computer manufacturers, Dell is more of an assembler and marketer than a producer. In response to customer demand, they create personalised computers, based upon a standard set of components. These items, such as the central processor, screen, graphics card, hard drive, battery etc, are produced by a range of suppliers, typically at least fifteen, and sometimes over thirty, dispersed geographically around the world. These are then assembled, quality controlled, packed and shipped. Usually the shipping is itself outsourced. Therefore, this is a multi-linked supply chain, as shown in Figure 2.

Such a supply chain has been twenty years in development and is still evolving. For example, it is worth noting that in response to customer demand, Dell has now turned its attention to its sales chain through the introduction of sales through retailers, something which of course would have been unthinkable over twenty years ago when the company was founded on the direct sale approach. This shows that world class companies are willing to cull ‘sacred cows', if necessary.

Secondly, Vodafone, the world's leading mobile telecommunications company with a significant presence in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia Pacific and the US through subsidiaries, joint ventures, associated undertakings and investments. Vodafone does not really manufacture anything itself. In 2006/7 they spent more than £20bn on purchasing products and services. They source equipment for their networks and the handsets they sell from third party manufacturers who themselves source components and assemble products from their suppliers. This is a huge procurement process the success of which, in terms of cost, quality and timeliness, can have a significant impact upon the overall corporate results. One way they handle this is to only have a direct relationship with their prime suppliers and in turn they expect their prime suppliers to manage the downstream chain.

Comparing the above examples to the early days of modern business such as Ford Motor Company or GE, where most, if not all, of the supply chain was fully in-house, it is clear that in the space of a single lifetime, business has come a long way to the point that supply chains are global and consist of multiple actors. On the one hand this brings the benefit of specialisation and scale, as predicted by Adam Smith, the Scottish eighteenth century economist. His theory3, ground breaking at the time, was that division of labour (and hence specialisation) would bring significant increases in production and of course, this theory has been since well proven. On the other hand, as the supply chain is broken down into smaller and smaller pieces how is it possible to manage the resulting chain in an effective and efficient manner?

Further evidence has recently emerged that there will be an increased focus upon a networked and interconnected environment in the business world of the future. This is in the form of collaborative working, which has been termed ‘Wikinomics' by Tapscott and Williams in their book of the same name4. This is exemplified by the likes of MySpace, YouTube, Linux and Wikipedia and shows the power of millions of people from around the world working together. It is not clear where this will lead, but one thing is for sure, modern leaders and managers will require the key business skill of managing interconnectedness.

Therefore the evidence is clear fund managers will be operating within an ever increasingly complex and multi-sourced world. To borrow a term from the internet revolution, it could even be called Sourcing 2.0. Operational specialists must be very comfortable with managing such an environment.

SOURCING WITHIN THE INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT INDUSTRY

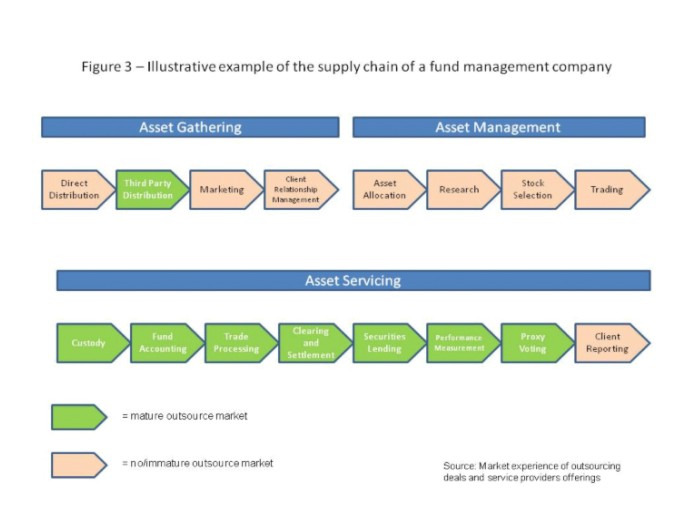

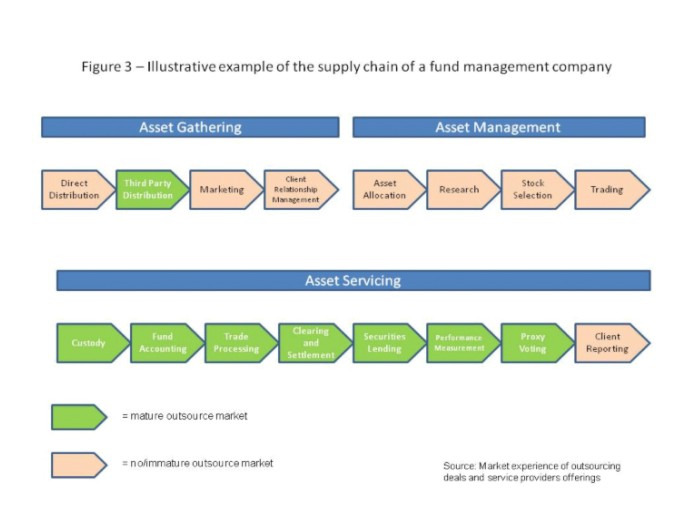

The level of disaggregation of the investment management supply chain partly depends upon the region of the world that we consider. In general, it is accepted that the US is most advanced in the use of outsourcing, followed by both Europe and the Middle East with Asia the least developed. Therefore it is not easy to give a one model fits all. However, Figure 3 shows how the functions of a new investment management company could be practically sourced today. The definition of sourced used for Figure 3 is that the fund manager can ask a separate company, not linked to the fund manager to actually undertake the activity (rather than just provide the technology platform).

The first point to note from Figure 3 is that even at this simplified depiction, there are a number of functional steps that need to be conducted. This already requires a level of competence to glue all this together, even if there were to be no more progress of extending the supply chain. Secondly, it is probably not surprising to see that so far there has been greater penetration into the back office for the use of outsourcing. There has been demand and supply at work here.

The often quoted leading demand arguments5 are that from the perspective of the fund managers they are likely to:

- improve their profitability through greater emphasis upon investment performance and client service i.e. areas where they need to build their own competence. Interestingly, there are few independent quantitative studies that have been able to prove (or disprove, depending upon your perspective) that this result is actually achieved in practice, though this has not halted the trend nor reversed many previous outsourcing decisions.

- Achieve financial savings. The reality is that it is more likely to achieve a move to a more variable cost base rather than see immediate or significant cost savings compared to in-house, though the avoidance of large in-house capital expenditure should not be underestimated

- Improve service levels. Again, difficult to quantify since there are very few published studies of service levels pre and post an outsource. However, the sometimes variable quality of service delivery from the service provider community will be known to a number of operational professionals who buy these services

- Leverage the investment and functionality built by service providers for their client base. This is a tangible benefit, for example, SWIFT20022, MiFID and increased derivative usage, all require investment, so why not achieve this collaboratively through common service providers.

These third party securities processing companies are themselves considering what is core to their business and what in turn they should outsource. They are increasingly recognising that pure processing is not the only future battle ground and that to a certain extent they are ‘information brokers'. This is analogous to the Dell and Vodafone examples mentioned earlier where Dell and Vodafone only deal with their prime suppliers. The fund manager outsources activities to their prime suppliers e.g. global custodians. In turn, they then expect these prime suppliers to work out how best to deliver. Either the prime suppliers produce the goods themselves or they look to others eg they outsource, offshore. Within the fund industry this environment is less developed than the likes of computer and telecoms business. However, there is no obvious reason to suggest why the fund industry will not develop in a similar fashion. If this does happen, then this will result in an even further extended supply chain for fund managers to consider.

MANAGING THE SUPPLY CHAIN

However the sourcing picture looks in the future, it is uncontroversial to say anything other than it will look different to the past. As such, the importance of managing the supply chain (or providing the ‘glue') is both clear to see and becoming an increasingly important competence in running a modern fund management company. The military have always known the importance of supply chain management. In any form of advance, lasting success can often come down to how well the supply chain has been set up to support the forward parties. A poor design or execution and the front line can quickly find themselves in difficulty. Business has adopted this mindset and it becomes a source of competitive differentiation.

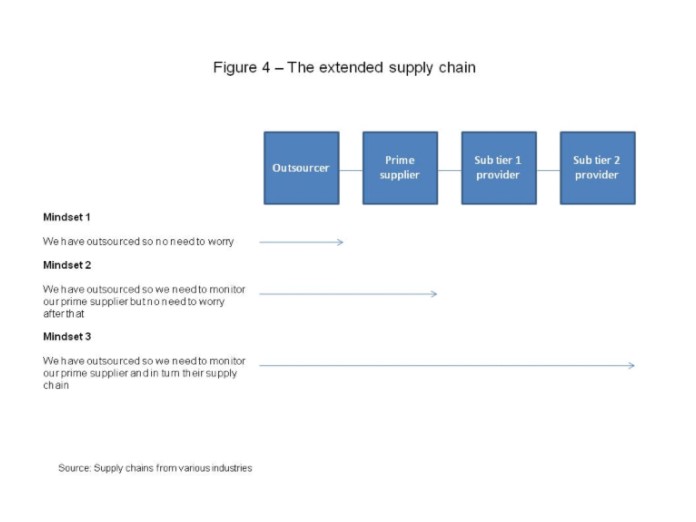

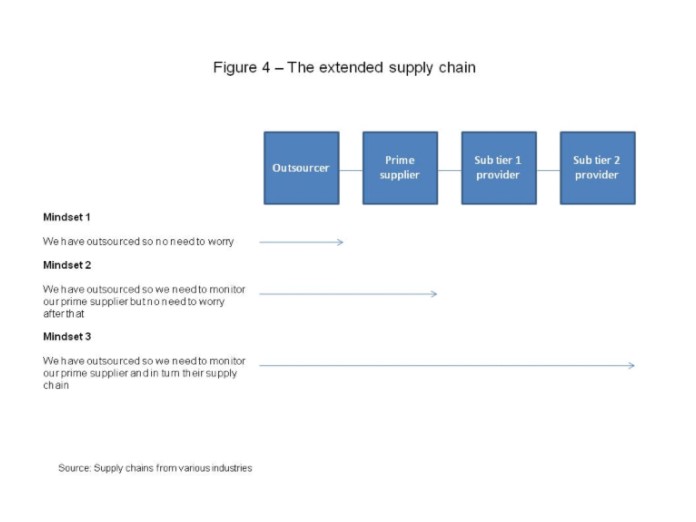

Before looking at the tools that can help manage the supply chain, it is important to first deal with the fundamental subject of Mindset. Figure 4 shows three example mindsets.

There is no simple answer as to which mindset to adopt, it is situational. However, the thought process should always consider all three. Too often, Mindset 1 is adopted, even though we know that Regulators do their best to encourage at least Mindset 2, through their often quote maxim of ‘You can outsource the activity but not the responsibility'. Furthermore there are pressures from other directions that encourage a move towards Mindset 3. For example, the need to demonstrate Corporate and Social Responsibility has seen significant focus over the past five years. Therefore can a fund manager that outsources some of its activities really afford to close its mind to the full supply chain that sits behind the scenes? In today's world, the answer is simple – No.

Therefore as fund managers slowly outsource more and more activities, hollowing themselves out as described by Ridderstrale and Nordstrom6, it is almost inevitable that Mindset 3 will become the predominant choice. This will demand change and hard work from fund managers and of equal importance, a willingness from service providers to be more open than they have been in the past.

TOOLS

Over the past several decades a whole industry and associated tools have grown up around the supply chain industry. Some companies, such as Coca Cola, even have functions called Supply Chain Operations. Business experience is growing but it is not clear that this practical experience is permeating (through the movement of ideas and/or employees) into the investment management industry at any real speed. For example, The Supply Chain Management Institute7 recommends a process that consists of eight elements:

- Customer Relationship Management

- Supplier Relationship Management

- Customer Service Management

- Demand Management

- Order Fulfilment

- Manufacturing Flow Management

- Product Development and Commercialisation

- Returns Management.

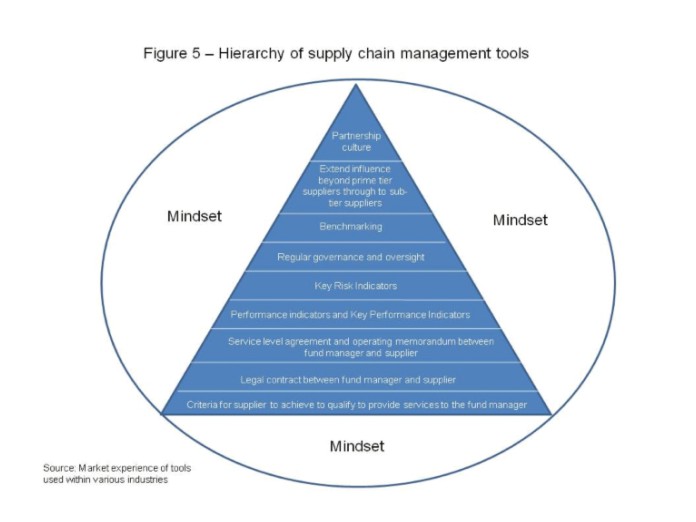

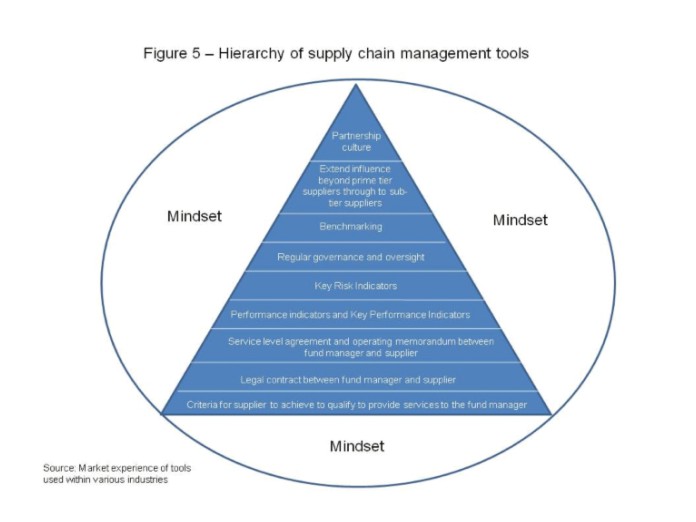

To borrow a theme from Maslow8, there is a hierarchy of tools that can be used by fund managers to cope with this hollowed out operating model. These are shown in Figure 5.

When a fund manager undertakes an activity itself in one place, it can be said, or believed, it is has full control. When the same fund manager starts to source activities from third parties or geographically dispersed locations then the nature of control over the activity changes. This results in reduction and addition, meaning:

- reduction: possibility to reduce the number of staff, activities, risk and cost within the fund management company

- addition: the introduction of professional supply chain management.

The tools described in Figure 5, are described in greater detail starting from the bottom and working upwards:

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

This is the factual due diligence process of selecting which service provider should be selected. This typically involves the Request For Proposal, supplier presentations, reference sites, negotiations, senior management meetings | Lack of recognition that a formal transparent selection process is necessary Political influence leads to skewed selection Not all stakeholder interests are taken into account Procurement is either over-centralised or undertaken purely within business units thus avoiding Group leverage Too much focus upon cost at the expense of other criteria | Through this disciplined process the most appropriate supplier, as assessed at that point in time, should be chosen whilst achieving an optimised financial result |

Stage: Legal contract between fund manager and supplier

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

The core legal agreement and any associated documentation | Poorly drafted contract creates ambiguity Legal process overtakes the establishment of a business relationship Different cultures have different views on legal approach i.e. general principles vs minutea | Establish a clear commercial relationship between the parties so that there is minimal scope for interpretation |

Stage: Service level agreement and operating memorandum between fund manager and supplier

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

Two documents (sometimes combined into one) that sets out the services that should be delivered by the supplier to the fund manager, how this will be done and to what standards | Poorly drafted with lack of precision Written in favour of one party more than the other Once written it is forgotten about and never referred to | Clearly document and communicate what the fund manager and the supplier expect of each other in terms of service delivery. This allows a benchmark against which to assess actual service delivery |

Stage: Performance Indicators (PIs) and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

A document that sets out both input measures and output measures. Correct achievement of these measures should result in the underyling service meeting expectations. Sometime incentives and penalties can be linked to the achievement of these measures | Too much focus on output measures rather than input measures Indicators are not SMART ie specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, timely Drive the wrong behaviour Too infrequent monitoring Belief that the indicators are the only aspects of the relationship that should be monitored Service provider not sufficiently transparent about their performance | A set of clear of limited measures that will demonstrate the performance of the service provider. A sub section of these Performance Indicators can be classified as ‘Key’ and as such these can have financial conditions attached to the achievement or not of these ‘Key’ items. They are primarily backwards looking ie assess the service after delivery. |

Stage: Key Risk Indicators (KRIs)

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

A document that set outs indicators to be monitored between the fund manager and service provider specially focused on areas of risk management. This is complementary to the PIs and KPIs | KRIs do not exist and are not systematically measured Indicators are insufficiently forward looking Drive the wrong behaviour Too infrequent monitoring Belief that FRAG21/SAS70 are sufficient indicators Even if collected, the indicators are given insufficient prominence Service provider not sufficiently transparent about the risks Insufficient consideration given to operational risk and associated capital requirements | Provide greater insight and sophistication to the monitoring of the relationship between fund manager and service provider. Given that risk is to do with something that could happen in the future, the KRIs need to act as a forward looking radar, though they can draw upon previous trend data |

Stage: Regular governance and oversight

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

Reports, scorecards and meetings (formal and informal) between client and supplier to manage the commercial relationship on a day to day tactical basis plus also consider strategic matters between both firms. This is the forum to consider change management matters. All of this is primarily achieved through a Vendor Management Unit, however it should be supported by other functions of the fund manager | Seen as an administrative function Inappropriately/insufficiently staffed The service provider is opaque about their performance and issues Service provider fails to recognise that the funds/clients that they administer belong to the fund manager and as such the fund manager are entitled to full transparency The relationship management functions of the service provider or fund manager ‘block’ proper conversations between the operational specialists | Ensure that on an ongoing basis the supplier chosen through the selection process remains the most appropriate. Provide the discipline of regular reviews and ensure that both parties remain fully knowledgeable about the underlying processes taking place and that they function correctly |

Stage: Benchmarking

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

Comparing the performance of the service provider with a relevant benchmark | Difficult to find relevant and agreed benchmarks and benchmark providers Only used as indicative rather than legally binding | Brings an element of objectivity and independence into the relationship between the fund manager and service provider |

Stage: Extend influence beyond prime tier suppliers through to sub-tier suppliers

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

Fund manager manages not only the prime supplier but also demonstrates an interest in the sub tier supplier network and expects both information and a certain degree of influence | Not considered important by the fund manager or the prime tier supplier i.e. lack of Mindset 3 thinking Fund manager does not have the competence to look beyond the prime tier supplier Inappropriate belief that the fund manager having an ‘interest’ in the extended supply chain means bureaucratic control | Fund manager remains fully knowledgeable of the complete supply chain, ensures corporate social responsibilities are delivered, early identification of any problems |

Stage: Partnership culture

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

Moving to a mindset of open and transparent communication, sharing of each others strategies and even financials | Only lip service is given to the term ‘partnership’ Fund manager fails to recognise they have to play a full and equal role to play in creating the appropriate culture The service provider is opaque about their performance and issues | Recognise that the interests of both fund manager and supplier are linked and working in a seamless fashion generates positive outcomes |

VENDOR MANAGEMENT UNIT (VMU)

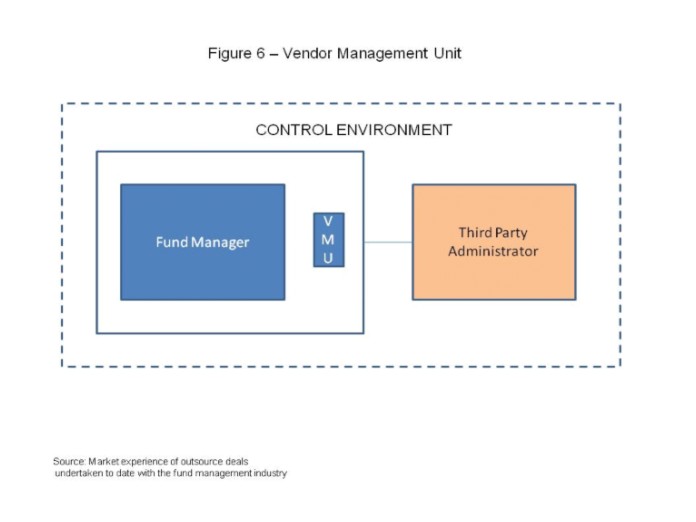

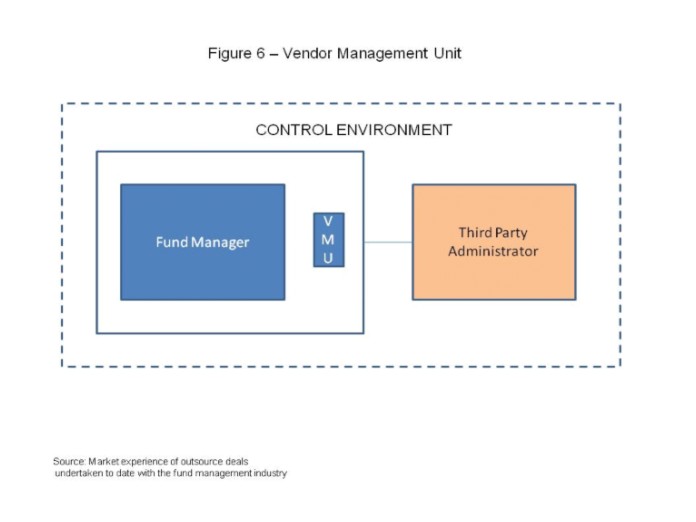

It is worth saying a little more about the VMU. Experience of outsource deals over the past ten years shows that typically the importance of the VMU is undervalued at the start of an outsource relationship. With the passing of time, the fund manager and the service provider both recognise the VMU's importance. This is the unit that is part of the fund manager and functions between the fund manager and the service provider, see Figure 6.

Its focus is to be the champion of the supply chain process and will have prime responsibility for utilising the tools described in Figure 4 with the ultimate objective of ensuring that the quality of output from the downstream supply chain meets expectations. . An analogy for the VMU is the tow bar between a car and a caravan. It is part of the car, and though small in size it fulfils a vital role to keep the caravan linked to the car and both going in the same direction. It offers flexibility and firmness combined.

Typically, the size of the VMU is around 5% - 10% of the business that the VMU is monitoring. One of its key focuses is data, both transactional data since this is what typically flows between the fund manager and the service provider plus management information. At the heart of a professionally run supply chain, measurement is key in maintaining the degree of control that a fund manager should or wants to have. This theme runs throughout Figure 4 and is all about gaining transparency. The old maxim of ‘what gets measured gets done' is as relevant today as ever before. As such, the VMU is ideally placed execute this measurement and to contribute to ensuring the full Control Environment is functioning properly.

Staffing the VMU is a challenge since it is necessary to have people who understand the full supply chain even though they are not undertaking all of the activities. Also, since the VMU is typically small in size it does not give much opportunity for the direct management of staff. Instead there is a greater need to be able to utilise more sophisticated forms of influencing people, i.e. through the use of a high EQ – emotional intelligence. Therefore finding staff who have the combination of technical knowledge and emotional competence is not easy to come by and need to be rewarded accordingly.

Having explained the role of the VMU, it is important to recognise however that other key functions of the fund manager must have healthy relationships with their opposite numbers at the service provider. Example functions are Compliance and Risk Management. This will help to ensure that the broader Control Environment, as shown in Figure 6 is achieved. This would be complementary to the daily operational control and communication undertaken by the VMU.

OFFSHORING

Offshoring is a phenomenon that has grown in significance over the past ten years. The fund management industry has not been immune to this development. For example, India and Poland are just two countries that have benefited from the move of some functions from countries such as Ireland, Luxembourg, the US and the UK. However in general terms, the approach to managing an offshoring should be largely the same as that for an outsource. Looking at Figure 4 it can be argued that it in such a situation it is even more important to adopt Mindset 3, i.e. to look through the complete supply chain. This is especially so given the relatively early stages of offshoring within the investment management industry. Maybe in twenty years time greater experience and comfort will have been gained with the concept of offshoring, but for now it is probably appropriate to take a prudent and measured approach.

OUTSOURCING WITHIN THE SAME COMPANY

Often outsourcing within the same company is viewed differently from appointing an external firm. This should not be the case. In can be tempting to say that because the activity is undertaken within the same group then for some reason it is acceptable to take a more relaxed approach to getting the most out of the relationship. However, that mindset does not follow the maxim of ‘survival of the fittest' since it potentially allows lower standards to become the norm which ultimately does not lead to world class service to end clients. Since this deterioration can sometimes take a while to show up, it is quite possible to experience push back when attempting to install a regime equivalent to that for an external outsource.

CONCLUSION

Business, in general, has come a long way in the last one hundred years from a model where everything was produced and manufactured within single companies to a distributed sourcing model that stretches the globe. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, production was very fragmented and there were few entities where a product was completely produced within one organisation. To a certain extent the Industrial Revolution can be thanked for leading to the amalgamation of activities within single companies, and this of course continued with significant growth in the early twentieth century. Therefore outsourcing is simply taking us full circle to a situation where supply chains are once again made up of a number of different parties. Today, as Peter Drucker says, ‘In this emerging competitive environment, the ultimate success of the business will depend upon management's ability to integrate the company's intricate network of business relationships'9

There is a whole range of sourcing strategies spread across the globe. Barriers to global sourcing have indeed significantly reduced, as described by Thomas Friedman in his book ‘The World is Flat'10. There would seem to be further scope to dis-aggregate the current business of fund managers, even for those most adventurous ones who are way ahead of others. There is little evidence to suggest that as an industry the point where dis-economies are encountered has been reached. As such, the message must be that there is further yet to run on achieving the optimal global sourcing strategy.

Irrespective of whether these sourcing trends are viewed as threats or opportunities, fund managers must embrace them in one way or another. What evidence that does exist suggests that there is some distance yet to travel before fully professional supply chain management is being practised through the fund management community. There are a range of tools available and fund managers must increasingly recognise that one of their core competencies should be the ability to manage a fragmented network of service providers. However, this is not a case of painting by numbers. Their needs to be a fundamental mindset appreciation of supply chain management. Only then will the tools be most effective.

REFERENCES

1. Information gathered from publicly available information including www.dell.com

2. Information gathered from publicly available information including www.vodafone.com

3. Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776

4. Wikinomics by Don Tapscott and Anthony D Williams, 2007

5. Global Investor Operational Outsourcing Survey 2005

6. Jonas Ridderstrale and Kjell Norstrom, Funky Business Forever 2008

7. www.scm-institute.org

8. Abraham Maslow, A Theory of Human Motivation, 1943

9. Peter F Drucker, Management’s New Paradigm, Forbes Magazine, 1995

10. Thomas Friedman, A Brief History of the Globalised World in the 21st Century, 2006

This site, like many others, uses small files called cookies to customize your experience. Cookies appear to be blocked on this browser. Please consider allowing cookies so that you can enjoy more content across fundservices.net.

How do I enable cookies in my browser?

Internet Explorer

1. Click the Tools button (or press ALT and T on the keyboard), and then click Internet Options.

2. Click the Privacy tab

3. Move the slider away from 'Block all cookies' to a setting you're comfortable with.

Firefox

1. At the top of the Firefox window, click on the Tools menu and select Options...

2. Select the Privacy panel.

3. Set Firefox will: to Use custom settings for history.

4. Make sure Accept cookies from sites is selected.

Safari Browser

1. Click Safari icon in Menu Bar

2. Click Preferences (gear icon)

3. Click Security icon

4. Accept cookies: select Radio button "only from sites I visit"

Chrome

1. Click the menu icon to the right of the address bar (looks like 3 lines)

2. Click Settings

3. Click the "Show advanced settings" tab at the bottom

4. Click the "Content settings..." button in the Privacy section

5. At the top under Cookies make sure it is set to "Allow local data to be set (recommended)"

Opera

1. Click the red O button in the upper left hand corner

2. Select Settings -> Preferences

3. Select the Advanced Tab

4. Select Cookies in the list on the left side

5. Set it to "Accept cookies" or "Accept cookies only from the sites I visit"

6. Click OK

Martyn Cuff is Head of Operations for Allianz Global Investors Europe. The Operations team covers Mutual Funds, Segregated Accounts and Fund Registration and is based in a number of key European locations. Martyn has 21 years experience within the investment management industry. During this time he has operated within both the front and back office at private client and institutional fund managers. Prior to joining AGI Europe, he was a founding partner at a boutique investment consulting company, CSTIM, and before that he worked at Ernst & Young. His early career was spent at Barclays. Martyn is an active member of the European Fund Industry, contribution to various forums and publications.

ABSTRACT

From where fund management companies obtain their operational support has become a more complex question over the past twenty years. To a large extent this is simply a reflection of developments seen in the broader business world in terms of changes to business models and the need for operating models to keep in step. Allied to this is the greater range of sourcing options now open to companies, largely on the back of the technology revolution. It is clear that further change lies ahead with business models becoming ever more specialised and collaborative.

Coping with these developments puts a lot of pressure upon fund managers to ‘glue’ together these more fragmented operational elements to achieve control, efficiency, risk management and output yet maintaining sufficient flexibility to adapt an ever increasing pace of business and consumer change. Not all operational departments are equipped with the sufficient competencies and processes to undertake proper supply chain management and thus get the most out of these new sourcing options.

This article firstly looks at the broader sourcing environment and then considers what fund managers need to have in place to cope with the business and operating changes that are taking place.

Keywords: fund management, operating models, collaborative, supply chain management, sourcing options.

INTRODUCTION

Companies are made up of individual functions that must not only be successful in their own right but also work in an aligned fashion or ‘glued’ together to deliver on the corporate objectives. This kind of total system thinking, or to use the more formal description of supply chain management, is key to achieving world class operations. The problem is that this thinking is not always valued within fund management companies particularly where outsourcing has taken place. Instead, fund managers have been known to point their finger at that their outsource partners where results are not as desired. Whilst there is undoubted evidence that the service provider community need to improve the quality of their services, fund managers also need to look at themselves to see whether they are taking the lead to put in place the right mindset and tools that promotes the appropriate environment.

Over the last twenty five years there have been a range of approaches adopted to answer the question of ‘How best to arrange our sourcing’ within fund managers. In the 1980s, the sourcing question was not top of the agenda, since the majority of fund management companies did most things themselves. Even where it was considered, thought did not stretch much further than outsourcing of custody. Since that time, there has been an exponential increase in the rate of sourcing consideration. In the early days in fact it was not ‘sourcing’, the description was simply ‘build, buy or outsource’. Nowadays the in-vogue terminology is ‘sourcing’ i.e. ‘what is your global sourcing approach?’ Figure 1 represents in simple terms how this trend is accelerating.

Supply chain management only becomes a key necessity if it is true that this increased complex sourcing picture is going to be part of future management challenges within our industry. There are two sources of evidence to draw upon to support this view: firstly within the fund management industry and secondly the broader business environment.

WITHIN THE FUND MANAGEMENT INDUSTRY

Asking a few questions shows that the asset management industry is already on the journey to a more fragmented operating environment:

- When was the last time a fund manager embarked upon a back or middle office system development and build? If not for some years then one of the reasons is quite possibly that this system build has been outsourced to third party software vendors e.g. Sungard, DST, Simcorp, Bloomberg etc through the usage of their generic products

- When was the last time that a fund manager decided to build and run his own data centres and business continuity facilities? If not, then there is a fair chance that the reliance is placed an external third party IT company

- Was offshoring seriously considered ten years ago? Not in a widespread fashion, but its more difficult to ignore the subject today

- When was the last time that fund managers were looking to bring back in-house activities that were undertaken by third parties? In general not for some years which indicates at least some level of willingness to leave these activities with others

The asset management industry is at the leading edge in some subjects such as allocation of capital to maximise return, however it is not always first to test out new ways of running its own businesses for maximum efficiency. Therefore it is worth looking at the wider business environment to identify any indication about the future development of sourcing - Dell1 and Vodafone2 are useful examples.

Like most computer manufacturers, Dell is more of an assembler and marketer than a producer. In response to customer demand, they create personalised computers, based upon a standard set of components. These items, such as the central processor, screen, graphics card, hard drive, battery etc, are produced by a range of suppliers, typically at least fifteen, and sometimes over thirty, dispersed geographically around the world. These are then assembled, quality controlled, packed and shipped. Usually the shipping is itself outsourced. Therefore, this is a multi-linked supply chain, as shown in Figure 2.

Such a supply chain has been twenty years in development and is still evolving. For example, it is worth noting that in response to customer demand, Dell has now turned its attention to its sales chain through the introduction of sales through retailers, something which of course would have been unthinkable over twenty years ago when the company was founded on the direct sale approach. This shows that world class companies are willing to cull ‘sacred cows', if necessary.

Secondly, Vodafone, the world's leading mobile telecommunications company with a significant presence in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia Pacific and the US through subsidiaries, joint ventures, associated undertakings and investments. Vodafone does not really manufacture anything itself. In 2006/7 they spent more than £20bn on purchasing products and services. They source equipment for their networks and the handsets they sell from third party manufacturers who themselves source components and assemble products from their suppliers. This is a huge procurement process the success of which, in terms of cost, quality and timeliness, can have a significant impact upon the overall corporate results. One way they handle this is to only have a direct relationship with their prime suppliers and in turn they expect their prime suppliers to manage the downstream chain.

Comparing the above examples to the early days of modern business such as Ford Motor Company or GE, where most, if not all, of the supply chain was fully in-house, it is clear that in the space of a single lifetime, business has come a long way to the point that supply chains are global and consist of multiple actors. On the one hand this brings the benefit of specialisation and scale, as predicted by Adam Smith, the Scottish eighteenth century economist. His theory3, ground breaking at the time, was that division of labour (and hence specialisation) would bring significant increases in production and of course, this theory has been since well proven. On the other hand, as the supply chain is broken down into smaller and smaller pieces how is it possible to manage the resulting chain in an effective and efficient manner?

Further evidence has recently emerged that there will be an increased focus upon a networked and interconnected environment in the business world of the future. This is in the form of collaborative working, which has been termed ‘Wikinomics' by Tapscott and Williams in their book of the same name4. This is exemplified by the likes of MySpace, YouTube, Linux and Wikipedia and shows the power of millions of people from around the world working together. It is not clear where this will lead, but one thing is for sure, modern leaders and managers will require the key business skill of managing interconnectedness.

Therefore the evidence is clear fund managers will be operating within an ever increasingly complex and multi-sourced world. To borrow a term from the internet revolution, it could even be called Sourcing 2.0. Operational specialists must be very comfortable with managing such an environment.

SOURCING WITHIN THE INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT INDUSTRY

The level of disaggregation of the investment management supply chain partly depends upon the region of the world that we consider. In general, it is accepted that the US is most advanced in the use of outsourcing, followed by both Europe and the Middle East with Asia the least developed. Therefore it is not easy to give a one model fits all. However, Figure 3 shows how the functions of a new investment management company could be practically sourced today. The definition of sourced used for Figure 3 is that the fund manager can ask a separate company, not linked to the fund manager to actually undertake the activity (rather than just provide the technology platform).

The first point to note from Figure 3 is that even at this simplified depiction, there are a number of functional steps that need to be conducted. This already requires a level of competence to glue all this together, even if there were to be no more progress of extending the supply chain. Secondly, it is probably not surprising to see that so far there has been greater penetration into the back office for the use of outsourcing. There has been demand and supply at work here.

The often quoted leading demand arguments5 are that from the perspective of the fund managers they are likely to:

- improve their profitability through greater emphasis upon investment performance and client service i.e. areas where they need to build their own competence. Interestingly, there are few independent quantitative studies that have been able to prove (or disprove, depending upon your perspective) that this result is actually achieved in practice, though this has not halted the trend nor reversed many previous outsourcing decisions.

- Achieve financial savings. The reality is that it is more likely to achieve a move to a more variable cost base rather than see immediate or significant cost savings compared to in-house, though the avoidance of large in-house capital expenditure should not be underestimated

- Improve service levels. Again, difficult to quantify since there are very few published studies of service levels pre and post an outsource. However, the sometimes variable quality of service delivery from the service provider community will be known to a number of operational professionals who buy these services

- Leverage the investment and functionality built by service providers for their client base. This is a tangible benefit, for example, SWIFT20022, MiFID and increased derivative usage, all require investment, so why not achieve this collaboratively through common service providers.

These third party securities processing companies are themselves considering what is core to their business and what in turn they should outsource. They are increasingly recognising that pure processing is not the only future battle ground and that to a certain extent they are ‘information brokers'. This is analogous to the Dell and Vodafone examples mentioned earlier where Dell and Vodafone only deal with their prime suppliers. The fund manager outsources activities to their prime suppliers e.g. global custodians. In turn, they then expect these prime suppliers to work out how best to deliver. Either the prime suppliers produce the goods themselves or they look to others eg they outsource, offshore. Within the fund industry this environment is less developed than the likes of computer and telecoms business. However, there is no obvious reason to suggest why the fund industry will not develop in a similar fashion. If this does happen, then this will result in an even further extended supply chain for fund managers to consider.

MANAGING THE SUPPLY CHAIN

However the sourcing picture looks in the future, it is uncontroversial to say anything other than it will look different to the past. As such, the importance of managing the supply chain (or providing the ‘glue') is both clear to see and becoming an increasingly important competence in running a modern fund management company. The military have always known the importance of supply chain management. In any form of advance, lasting success can often come down to how well the supply chain has been set up to support the forward parties. A poor design or execution and the front line can quickly find themselves in difficulty. Business has adopted this mindset and it becomes a source of competitive differentiation.

Before looking at the tools that can help manage the supply chain, it is important to first deal with the fundamental subject of Mindset. Figure 4 shows three example mindsets.

There is no simple answer as to which mindset to adopt, it is situational. However, the thought process should always consider all three. Too often, Mindset 1 is adopted, even though we know that Regulators do their best to encourage at least Mindset 2, through their often quote maxim of ‘You can outsource the activity but not the responsibility'. Furthermore there are pressures from other directions that encourage a move towards Mindset 3. For example, the need to demonstrate Corporate and Social Responsibility has seen significant focus over the past five years. Therefore can a fund manager that outsources some of its activities really afford to close its mind to the full supply chain that sits behind the scenes? In today's world, the answer is simple – No.

Therefore as fund managers slowly outsource more and more activities, hollowing themselves out as described by Ridderstrale and Nordstrom6, it is almost inevitable that Mindset 3 will become the predominant choice. This will demand change and hard work from fund managers and of equal importance, a willingness from service providers to be more open than they have been in the past.

TOOLS

Over the past several decades a whole industry and associated tools have grown up around the supply chain industry. Some companies, such as Coca Cola, even have functions called Supply Chain Operations. Business experience is growing but it is not clear that this practical experience is permeating (through the movement of ideas and/or employees) into the investment management industry at any real speed. For example, The Supply Chain Management Institute7 recommends a process that consists of eight elements:

- Customer Relationship Management

- Supplier Relationship Management

- Customer Service Management

- Demand Management

- Order Fulfilment

- Manufacturing Flow Management

- Product Development and Commercialisation

- Returns Management.

To borrow a theme from Maslow8, there is a hierarchy of tools that can be used by fund managers to cope with this hollowed out operating model. These are shown in Figure 5.

When a fund manager undertakes an activity itself in one place, it can be said, or believed, it is has full control. When the same fund manager starts to source activities from third parties or geographically dispersed locations then the nature of control over the activity changes. This results in reduction and addition, meaning:

- reduction: possibility to reduce the number of staff, activities, risk and cost within the fund management company

- addition: the introduction of professional supply chain management.

The tools described in Figure 5, are described in greater detail starting from the bottom and working upwards:

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

This is the factual due diligence process of selecting which service provider should be selected. This typically involves the Request For Proposal, supplier presentations, reference sites, negotiations, senior management meetings | Lack of recognition that a formal transparent selection process is necessary Political influence leads to skewed selection Not all stakeholder interests are taken into account Procurement is either over-centralised or undertaken purely within business units thus avoiding Group leverage Too much focus upon cost at the expense of other criteria | Through this disciplined process the most appropriate supplier, as assessed at that point in time, should be chosen whilst achieving an optimised financial result |

Stage: Legal contract between fund manager and supplier

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

The core legal agreement and any associated documentation | Poorly drafted contract creates ambiguity Legal process overtakes the establishment of a business relationship Different cultures have different views on legal approach i.e. general principles vs minutea | Establish a clear commercial relationship between the parties so that there is minimal scope for interpretation |

Stage: Service level agreement and operating memorandum between fund manager and supplier

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

Two documents (sometimes combined into one) that sets out the services that should be delivered by the supplier to the fund manager, how this will be done and to what standards | Poorly drafted with lack of precision Written in favour of one party more than the other Once written it is forgotten about and never referred to | Clearly document and communicate what the fund manager and the supplier expect of each other in terms of service delivery. This allows a benchmark against which to assess actual service delivery |

Stage: Performance Indicators (PIs) and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

A document that sets out both input measures and output measures. Correct achievement of these measures should result in the underyling service meeting expectations. Sometime incentives and penalties can be linked to the achievement of these measures | Too much focus on output measures rather than input measures Indicators are not SMART ie specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, timely Drive the wrong behaviour Too infrequent monitoring Belief that the indicators are the only aspects of the relationship that should be monitored Service provider not sufficiently transparent about their performance | A set of clear of limited measures that will demonstrate the performance of the service provider. A sub section of these Performance Indicators can be classified as ‘Key’ and as such these can have financial conditions attached to the achievement or not of these ‘Key’ items. They are primarily backwards looking ie assess the service after delivery. |

Stage: Key Risk Indicators (KRIs)

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

A document that set outs indicators to be monitored between the fund manager and service provider specially focused on areas of risk management. This is complementary to the PIs and KPIs | KRIs do not exist and are not systematically measured Indicators are insufficiently forward looking Drive the wrong behaviour Too infrequent monitoring Belief that FRAG21/SAS70 are sufficient indicators Even if collected, the indicators are given insufficient prominence Service provider not sufficiently transparent about the risks Insufficient consideration given to operational risk and associated capital requirements | Provide greater insight and sophistication to the monitoring of the relationship between fund manager and service provider. Given that risk is to do with something that could happen in the future, the KRIs need to act as a forward looking radar, though they can draw upon previous trend data |

Stage: Regular governance and oversight

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

Reports, scorecards and meetings (formal and informal) between client and supplier to manage the commercial relationship on a day to day tactical basis plus also consider strategic matters between both firms. This is the forum to consider change management matters. All of this is primarily achieved through a Vendor Management Unit, however it should be supported by other functions of the fund manager | Seen as an administrative function Inappropriately/insufficiently staffed The service provider is opaque about their performance and issues Service provider fails to recognise that the funds/clients that they administer belong to the fund manager and as such the fund manager are entitled to full transparency The relationship management functions of the service provider or fund manager ‘block’ proper conversations between the operational specialists | Ensure that on an ongoing basis the supplier chosen through the selection process remains the most appropriate. Provide the discipline of regular reviews and ensure that both parties remain fully knowledgeable about the underlying processes taking place and that they function correctly |

Stage: Benchmarking

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

Comparing the performance of the service provider with a relevant benchmark | Difficult to find relevant and agreed benchmarks and benchmark providers Only used as indicative rather than legally binding | Brings an element of objectivity and independence into the relationship between the fund manager and service provider |

Stage: Extend influence beyond prime tier suppliers through to sub-tier suppliers

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

Fund manager manages not only the prime supplier but also demonstrates an interest in the sub tier supplier network and expects both information and a certain degree of influence | Not considered important by the fund manager or the prime tier supplier i.e. lack of Mindset 3 thinking Fund manager does not have the competence to look beyond the prime tier supplier Inappropriate belief that the fund manager having an ‘interest’ in the extended supply chain means bureaucratic control | Fund manager remains fully knowledgeable of the complete supply chain, ensures corporate social responsibilities are delivered, early identification of any problems |

Stage: Partnership culture

Description | Typical problems | Benefit of proper use |

Moving to a mindset of open and transparent communication, sharing of each others strategies and even financials | Only lip service is given to the term ‘partnership’ Fund manager fails to recognise they have to play a full and equal role to play in creating the appropriate culture The service provider is opaque about their performance and issues | Recognise that the interests of both fund manager and supplier are linked and working in a seamless fashion generates positive outcomes |

VENDOR MANAGEMENT UNIT (VMU)

It is worth saying a little more about the VMU. Experience of outsource deals over the past ten years shows that typically the importance of the VMU is undervalued at the start of an outsource relationship. With the passing of time, the fund manager and the service provider both recognise the VMU's importance. This is the unit that is part of the fund manager and functions between the fund manager and the service provider, see Figure 6.

Its focus is to be the champion of the supply chain process and will have prime responsibility for utilising the tools described in Figure 4 with the ultimate objective of ensuring that the quality of output from the downstream supply chain meets expectations. . An analogy for the VMU is the tow bar between a car and a caravan. It is part of the car, and though small in size it fulfils a vital role to keep the caravan linked to the car and both going in the same direction. It offers flexibility and firmness combined.

Typically, the size of the VMU is around 5% - 10% of the business that the VMU is monitoring. One of its key focuses is data, both transactional data since this is what typically flows between the fund manager and the service provider plus management information. At the heart of a professionally run supply chain, measurement is key in maintaining the degree of control that a fund manager should or wants to have. This theme runs throughout Figure 4 and is all about gaining transparency. The old maxim of ‘what gets measured gets done' is as relevant today as ever before. As such, the VMU is ideally placed execute this measurement and to contribute to ensuring the full Control Environment is functioning properly.

Staffing the VMU is a challenge since it is necessary to have people who understand the full supply chain even though they are not undertaking all of the activities. Also, since the VMU is typically small in size it does not give much opportunity for the direct management of staff. Instead there is a greater need to be able to utilise more sophisticated forms of influencing people, i.e. through the use of a high EQ – emotional intelligence. Therefore finding staff who have the combination of technical knowledge and emotional competence is not easy to come by and need to be rewarded accordingly.

Having explained the role of the VMU, it is important to recognise however that other key functions of the fund manager must have healthy relationships with their opposite numbers at the service provider. Example functions are Compliance and Risk Management. This will help to ensure that the broader Control Environment, as shown in Figure 6 is achieved. This would be complementary to the daily operational control and communication undertaken by the VMU.

OFFSHORING

Offshoring is a phenomenon that has grown in significance over the past ten years. The fund management industry has not been immune to this development. For example, India and Poland are just two countries that have benefited from the move of some functions from countries such as Ireland, Luxembourg, the US and the UK. However in general terms, the approach to managing an offshoring should be largely the same as that for an outsource. Looking at Figure 4 it can be argued that it in such a situation it is even more important to adopt Mindset 3, i.e. to look through the complete supply chain. This is especially so given the relatively early stages of offshoring within the investment management industry. Maybe in twenty years time greater experience and comfort will have been gained with the concept of offshoring, but for now it is probably appropriate to take a prudent and measured approach.

OUTSOURCING WITHIN THE SAME COMPANY

Often outsourcing within the same company is viewed differently from appointing an external firm. This should not be the case. In can be tempting to say that because the activity is undertaken within the same group then for some reason it is acceptable to take a more relaxed approach to getting the most out of the relationship. However, that mindset does not follow the maxim of ‘survival of the fittest' since it potentially allows lower standards to become the norm which ultimately does not lead to world class service to end clients. Since this deterioration can sometimes take a while to show up, it is quite possible to experience push back when attempting to install a regime equivalent to that for an external outsource.

CONCLUSION

Business, in general, has come a long way in the last one hundred years from a model where everything was produced and manufactured within single companies to a distributed sourcing model that stretches the globe. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, production was very fragmented and there were few entities where a product was completely produced within one organisation. To a certain extent the Industrial Revolution can be thanked for leading to the amalgamation of activities within single companies, and this of course continued with significant growth in the early twentieth century. Therefore outsourcing is simply taking us full circle to a situation where supply chains are once again made up of a number of different parties. Today, as Peter Drucker says, ‘In this emerging competitive environment, the ultimate success of the business will depend upon management's ability to integrate the company's intricate network of business relationships'9

There is a whole range of sourcing strategies spread across the globe. Barriers to global sourcing have indeed significantly reduced, as described by Thomas Friedman in his book ‘The World is Flat'10. There would seem to be further scope to dis-aggregate the current business of fund managers, even for those most adventurous ones who are way ahead of others. There is little evidence to suggest that as an industry the point where dis-economies are encountered has been reached. As such, the message must be that there is further yet to run on achieving the optimal global sourcing strategy.

Irrespective of whether these sourcing trends are viewed as threats or opportunities, fund managers must embrace them in one way or another. What evidence that does exist suggests that there is some distance yet to travel before fully professional supply chain management is being practised through the fund management community. There are a range of tools available and fund managers must increasingly recognise that one of their core competencies should be the ability to manage a fragmented network of service providers. However, this is not a case of painting by numbers. Their needs to be a fundamental mindset appreciation of supply chain management. Only then will the tools be most effective.

REFERENCES

1. Information gathered from publicly available information including www.dell.com

2. Information gathered from publicly available information including www.vodafone.com

3. Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776

4. Wikinomics by Don Tapscott and Anthony D Williams, 2007

5. Global Investor Operational Outsourcing Survey 2005

6. Jonas Ridderstrale and Kjell Norstrom, Funky Business Forever 2008

7. www.scm-institute.org

8. Abraham Maslow, A Theory of Human Motivation, 1943

9. Peter F Drucker, Management’s New Paradigm, Forbes Magazine, 1995

10. Thomas Friedman, A Brief History of the Globalised World in the 21st Century, 2006